Modern European art movements such as constructivism, cubism, and futurism left a lasting influence on graphic design and the larger art world; this is evident in the poster for Exodus (1960) created by Saul Bass. Previous to the Exodus poster, in the 1950s, Bass was the creator of the first movie posters that migrated away from imagery or illustration of actors and invited abstract shapes and iconography to visually describe the advertised film (Meggs, 275). The film Exodus (1960), and the book that it was based on, is best described by David Ben-Gurion, Israel's first prime minister: “As a literary work, it isn’t much. But as a piece of propaganda, it’s the greatest thing ever written about Israel.” (Silver). The film romanticizes and dramatizes the creation of Israel and highlights the trauma and suffering of Jewish Holocaust survivors seeking refuge. Yet, it does so while erasing the ethnic cleansing incited onto the Palestinian population. Palestinians were, and continue to be more than seventy years later, displaced from their ancestral lands, subjected to violence, and forced into refugee camps, their homes, communities, and lives destroyed in the wake of Israel’s creation (Rought-Brooks). Exodus frames the conflict as a moral imperative for the Jewish people to have a homeland. Still, it largely ignores the reality that this "new beginning" for one body of oppressed people came at the direct expense of another.

Though the simple design of the poster may initially seem to be created with less heinous intentions than the movie, both are intended to advance a deadly and politically charged narrative. Bass’ graphic design reflects the principles of constructivism, an early 20th-century art movement emerging from the Russian Revolution, which emphasized modernity, geometric forms, abstraction, and functional design to create propaganda (Meggs, 219). Artists like El Lissitzky (who frequently visited the Bauhaus school) and Alexander Rodchenko used angular shapes and dynamic layouts to create striking visual works that were both visually attractive and practical for conveying their ideology (Meggs, 218 & 219). What Lissizky, Rodchenko, and Bass also have in common is using these techniques to create propaganda for regimes that sought to control and suppress the people's will. Their visually striking works reinforced totalitarian control by glorifying state power and masking systemic abuses, while simultaneously marginalizing opposing voices and enforcing harsh measures and punishments as deemed necessary for their societal progress. By idealizing unattainable goals, their propaganda fostered false hope and justified the sacrifices demanded by these regimes. In the Soviet Union, the ‘communist’ system devastated the nation through economic failures like famine, widespread human rights abuses, stifling of creativity, and long-term societal damage, leaving a legacy of mistrust and inefficiency (Brown). This is reflected in Bass’ poster within the iconography. The imagery on the poster is meant to invoke a sense of Zionist pride or righteousness for their cause. The black hands and fists clutching the rifle evoke the imagery of Jews fighting the Nazis in a 'moral' war. However, the film is set in 1948, the year Israeli prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, declared Israel a state, marking a pivotal moment in the displacement of Palestinians (U.S. State Department). Much like the Jewish people, who were not a militant group but civilians: men, women, and children, who were innocent when thrust into the Holocaust to experience unimaginable horrors, the Zionists inflict the same horrors on the non-militant civilian Palestinians.

Similar to constructivism, cubism also utilized geometric forms and abstraction, though its focus was on deconstructing and reinterpreting perspective. Human forms were often depicted with straight lines and angles in geometric patterns. Cubism rejected traditional artistic representation, breaking down the subjects into fragmented, abstract forms to explore multiple viewpoints within a single composition. Artists like Picasso and Braque sought to challenge the viewer’s perception of reality, offering a more dynamic and analytical approach to visual storytelling. While constructivist art served political agendas by championing social change, cubism contributed to the evolution of modern art by questioning the nature of reality and perception, often without a direct focus on political ideology. However, the political context in which many of these works were created, especially Picasso’s Guernica, drew on the art’s potential for social impact. Guernica, painted in 1937, directly addressed the horrors of the Spanish Civil War and the bombing of Guernica by Nazi forces, using abstraction to convey the trauma, chaos, and devastation of war. The poster from Exodus was greatly impacted by cubist techniques such as the sharp and unhuman-like angles of the hands and the oversimplification of the rifle. If the symbolism looks familiar to you it might be because it is reminiscent of what is known today as the Black Power Fist created in 1967 by Frank Cieciorka, also inspired by cubism. First appearing in 1910 by trade unionists, a raised fist has been used by groups all over the world to symbolize unity against oppression. However, it was widely popularized after 1948 by a Mexican print shop called Taller de Gráfica that used art to advance revolutionary social causes. This reflects the self-righteous narrative adopted by the Zionists, using the symbol to represent a struggle, one which they chose to enact, especially in the context of the film's portrayal with its disregard for Palestinian existence.

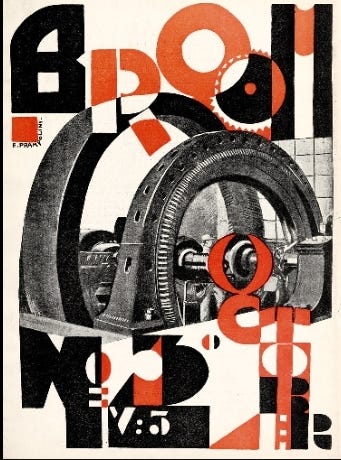

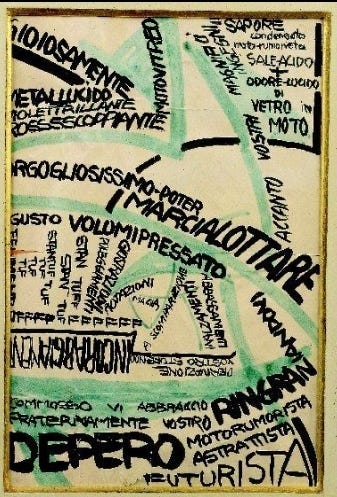

Futurism emerged before the World Wars, in 1909 when Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, an Italian poet and writer, published Futurist Manifesto. This manifesto called for the rejection of the past and emphasized the need for violent upheaval to solve societal grievances (Meggs, 192). At the time of its establishment, the futurists were majoritively writers though after being urged by a fellow member, Marinetti opened the futurists to artists of all mediums. This is relevant since because they were writers we have indisputable knowledge of who the futurists were, their societal goals, and ideologies. The inspiration behind the typeface of both the title ‘Exodus’ and the credits can be attributed to the Futurists as well. In Enrico Prampolini’s magazine cover for Broom (October 1922. vol.3 no.3), as well as many other graphic designs from the futurist, we see extremely bold lettering with no serifs. What makes Prampolini’s work uniquely comparative is the gap separating the tie, crossbar, and bowl from the body of the letter in both works. As for the typeface of the credits, having multiple, especially polarizing, typefaces on one design is also a futurist design trait as seen in works such as Fortunato Depero’s Marcialottare (Free-word composition letter addressed to Marinetti, 1916). Depero’s work features a similar oil pastel, or perhaps a child-like, look in his typeface similar to Bass. His work also features extremely bold lettering similar to other futurist works which may have also served as inspiration. As a part of their ideologies, the Futurists sought to break away from traditions and instead depict speed, technology, and the dynamic energy of modern life (Meggs, 192). These principles are evident in the Exodus poster, where the depiction of movement and the hyper-realistic flames at the bottom symbolize both motion and conflict, which, as previously mentioned, the Zionists used to elicit sympathy and evoke feelings of self-righteousness. It is important to acknowledge that, although Bass was Jewish and the futurists aligned with fascism in the years leading up to the Holocaust, this connection may not have been as significant a concern as it should have been.

While constructivism, cubism, and futurism all had principals based on straight lines and geometric shapes, like many art and graphic design movements, the chosen comparison all had intersecting ideologies or socio-political themes. It should be noted that none of these movements existed in a vacuum and all impacted one after the other, especially because they were close in time ranges. That being said, Bass was trained by György Kepes who had studied under László Moholy-Nagy (b., betty). Moholy-Nagy was a professor at the Bauhaus school and was also heavily influenced by constructivism (H. Moholy-Nagy). Saul Bass was extremely knowledgeable about the European modern art movements and drew inspiration from their works to create a design that was not only visually striking but also ideologically charged, using art to advance a politically driven narrative. In Bass's hands, these modernist techniques became tools of propaganda, reinforcing a narrative that ignored the experiences of Palestinians, and further demonstrated how art and design can be harnessed to manipulate, influence, and shape public perception.

Works Cited

b. , betty dept. of smoke & mirrors. “The Art of Saul Bass.” CAFILM, 7 June 2024, www.cafilm.org/the-art-of-saul-bass/#:~:text=Visually%2C%20a%20contemporary%20review%20of,Kepes%20who%20had%20studied%20under.

Bass, Saul. Poster for Exodus. 1960.

Brown, Archie. “The End of the Soviet Union.” Journal of Cold War Studies, vol. 17, no. 4, 2015, pp. 158–65. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26925548.

“Creation of Israel, 1948.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/creation-israel#:~:text=On%20May%2014%2C%201948%2C%20David,nation%20on%20the%20same%20day.

Cushing, Lincoln. “Movement Artist Frank Cieciorka Passes Away November 24, 2008.” Cieciorka Obituary 2009, 2008, www.docspopuli.org/articles/Cieciorka.html.

Meggs, Philip B., and Alston W. Purvis. Meggs’ History of Graphic Design. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

Moholy-Nagy, Hattula. “LÁSZLÓ MOHOLY-NAGY: A SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF THE ARTIST .” Moholy-Nagy Foundation. https://moholy-nagy.org/biography/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20Constructivists%20felt%20that%20a,wood%2C%20glass%2C%20and%20metal.

Preminger, Otto, director. Exodus. UA/Carlyle/Alpha, 1960.

Rought-Brooks, Hannah. “Gaza: Prelude to Genocide?” Socialist Lawyer, no. 51, 2009, pp. 22–25. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42950316.

Silver, Matthew. Our Exodus: Leon Uris and the Americanization of Israel’s Founding Story. Wayne State University Press, 2010.

Images

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937.

Saul Bass, Exodus, 1960

Frank Cieciorka, Stop the Draft Week, 1967.

Enrico Prampolini, Magazine Cover for Broom, October, 1922.

Fortunato Depero, Marcialottare (Free-word composition letter addressed to Marinetti), 1916

Thanks for sharing!! I wrote this for my history of graphic design class!