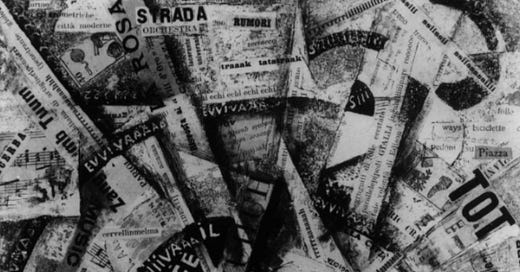

Carlo Carrà, Free-Word Painting—Patriotic Festival (1914). Mattioli collection, Milan. Pasted papers, charcoal, ink, gouache, and colored sparkles on board.

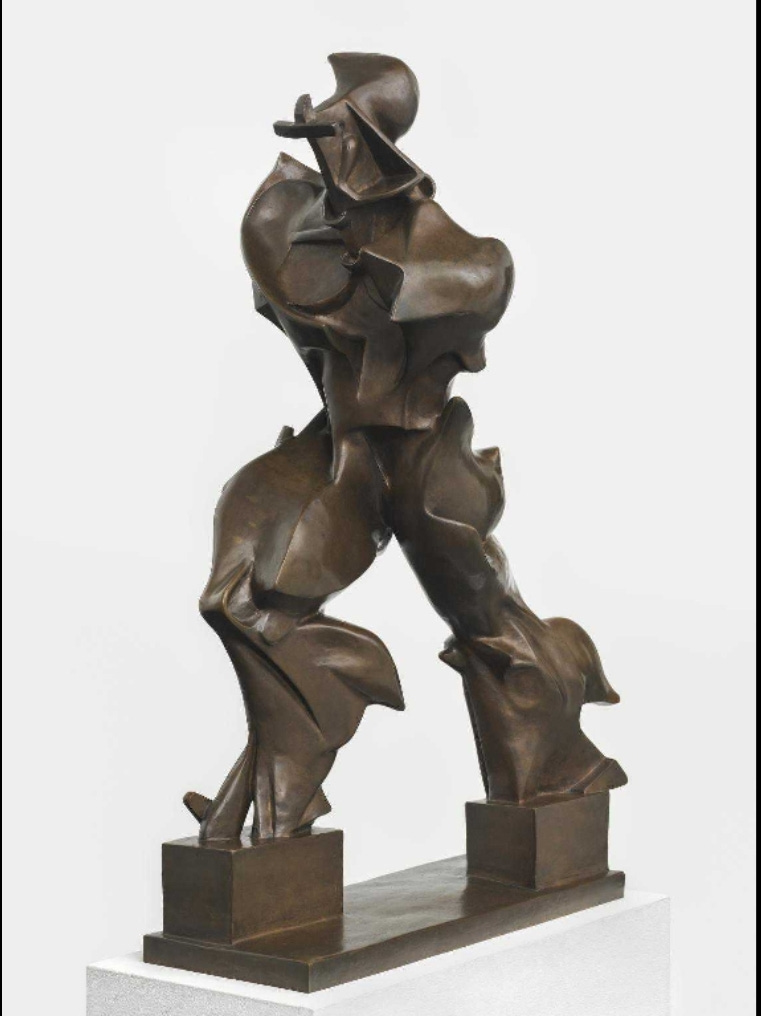

Umberto Boccioni Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913)

Rodin, Auguste. The Walking Man (L'homme qui marche). Modeled before 1900, cast before 1914, cast by Alexis Rudier.

Winged Victory of Samothrace. Hellenistic Period, c. 190 BCE. The Louvre Museum, Paris.

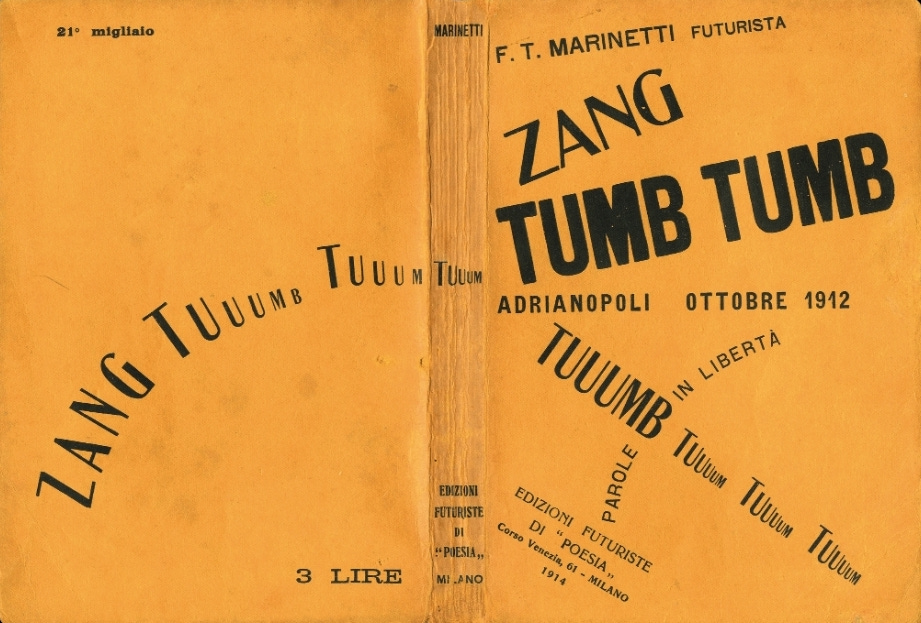

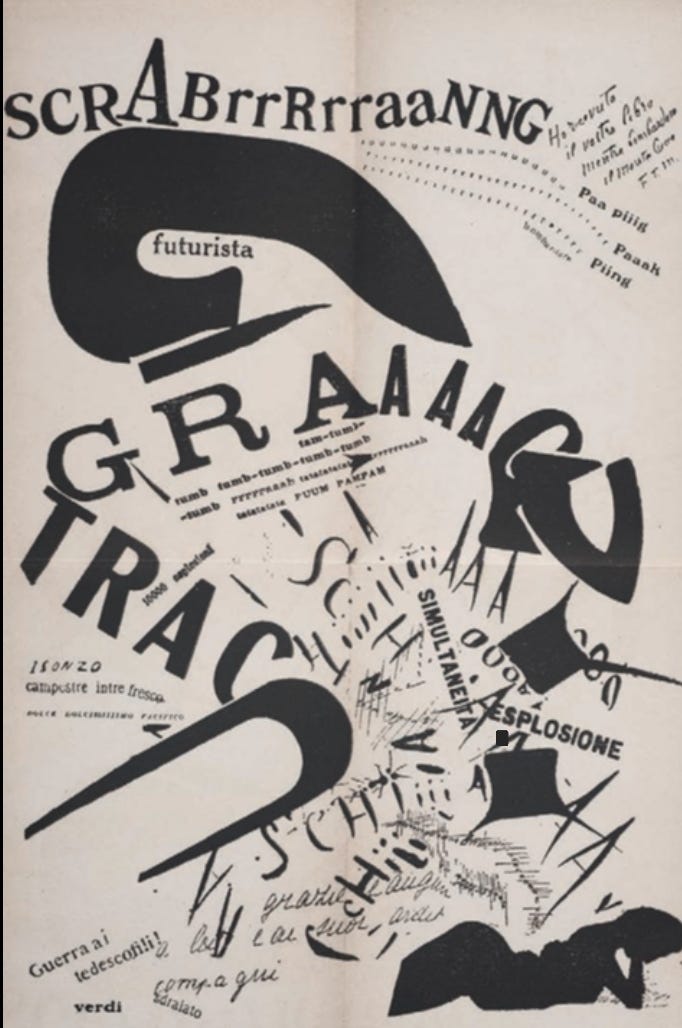

Filippo Marinetti, cover for Zang Tumb Tumb, 1912 (Meggs, pg. 272, illustration 13-8)

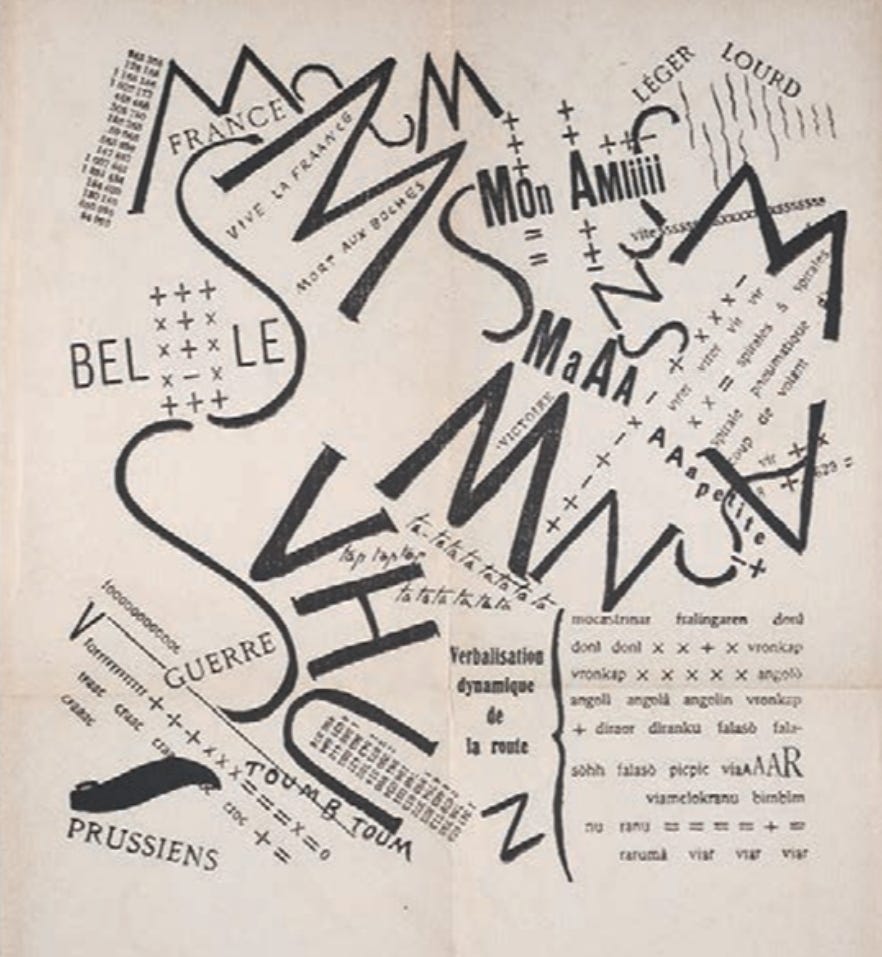

Filippo Marinetti, “Montagne + Vallate + Streets + Joffre” foldout from Les mots en liberté futurists, 1919 (Meggs, pg. 272 illustration 13-10)

Gino Severini, 1912, Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin, oil on canvas with sequins, 161.6 × 156.2 cm (63.6 × 61.5 in.), Museum of Modern Art, New York

Filippo Marinetti, foldout from Les mots en liberté futurists, 1919 (Meggs, pg. 27 illustration 13-11

The art movement futurism was founded in Italy by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909 and lasted until he died in 1944. Though it was clearly influenced stylistically by Neo-Impressionism and Cubism, it sought to break away from past traditions and instead depicts speed, technology, and the dynamic energy of modern life (Meggs, 2016). The movement's aesthetic characteristics of dynamic and chaotic typography are evident in its graphic design, the same elements that also influenced its visual arts, conveying a sense of modernity and motion.

While their title and obsession with technology may on the surface seem linked with progressive ideologies, the futurists were intangibly rooted in bigotry. The entanglement of fascism within futurism was apparent from the very first creative project, as the launch of the art movement began with Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto in 1909. He called for the rejection of the past and emphasized the need for violent upheaval to solve societal grievances (Meggs, 2016). Marinetti’s futurists were majoritively writers until he was urged by Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, and Luigi Russolo to recruit painters with a new manifesto: Manifesto of Futurist Painters (Poggi, 2002). The themes of modernity, motion, and new technologies as seen through the futurism art movement were hyperbole for their nationalistic, racist, privileged, classist, and nazi-like political acts and affiliations. Marinetti was even personally connected to Mussolini and predated his involvement with the Italian fascist party (Bowler, 1991). They had a long yet tense relationship. While they agreed on much, in the end, Mussolini and the nazis’ goal was a population of people without so-called ‘impurities’ that served the wealthy, able-bodied, white class, and stepped on anyone who differed in any way. When Marinetti’s art and the art of his colleagues was useful as propaganda it was recognized by Mussolini and the fascist party, though it was still art. Art, no matter who is creating it, will always be an inherent threat to nazis (or modern white-supremisits) because it embraces individuality which cannot co-occur with the ideology that one nation shares a single and ‘pure’ identity. At the summit of the nazi empire and within the last 10 years as the futurist art and political movement began to crumble, Mussolini allowed the nazis to show their "degenerate art" exhibition in Italy that included futurist works (Mosse, 1990; Tyson, 2011).

Futurist graphic design was deeply integrated with the movement's propaganda. It was used for exhibition programs, pamphlets, and poetry, making the visual aesthetic of the movement a direct part of its literature and creative projects (Meggs, 2016). Futurist graphic design is known for its bold use of sans-serif typeface, dynamic font changes, and curved lines, all often combined in a single piece. The typography and design were expressive, aiming to evoke the, previously mentioned, sense of motion and energy central to the movement. It was not just the content of the designs that was important, but their ability to embody the movement’s values: speed, technology, and a break from tradition. In their effort to break from tradition, the futurists borrowed from concrete poetry and, like all art movements, were influenced by what came before them. Many typefaces used resemble those found in Viennese Secessionist and De Stijl graphic design. They also coined the typography style parole in libertà (words in freedom). This style involved arranging words freely on the page, using multiple font sizes and angles to create a sense of movement and energy.

The following designs will be compared to their fine art (defined as non-utilitarian art in this context) counterparts to further emphasize their relation to one another within the futurist movement, as well as the ways in which they were used as propaganda: the cover for Zang Tumb Tumb, foldout from Les mots en liberté, and the foldout from Les mots en liberté titled Montagne + Vallate + Streets + Joffre.

Zang Tumb Tumb was written by Marinetti and was inspired by the conflict that he witnessed as a reporter for L'Intransigeant, a rightwing newspaper. It consists of concrete and sound poetry inspired by the sounds of war as seen in the graphic design on the cover of the art book. The onomatopoeia in combination with the parole in libertà typography featured on the cover represents the sounds and scenery of battle. Similarly, Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) depicts a humanoid body in motion as well as what may be their clothes or the air around them. Both artists’ portrayals of motion in art are linked to their obsession with oppressive concepts of social progression as well as technology and war. Boccioni shared the same fascist ideologies and disdain for history as Marinetti and even published a manifesto of his own (Antliff, 2000). Despite their mutual aggression of the past, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space shares strikingly similar attributes to the French stupor, Auguste Rodin’s, Walking Man and the ancient Greek sculpture Winged Victory of Samothrace. This is particularly interesting because in Marinetti’s very first manifesto he can be quoted writing:

“[...a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace]”.

Since Boccioni’s convictions were so closely aligned with Marinetti’s, it leaves little room for justification to create an alternative narrative other than the fact that Boccioni, while preaching futurist’s rejection of the past, was still deeply influenced by classical forms and the cultural heritage that futurism sought to disrupt. This speaks to how underdeveloped fascist ideologies are, as the social constructs they fought for in Italian society and beyond were ones they believed to be exempt from.

The graphic design work on the foldout from Les mots en liberté futurists (1919) and Carlo Carrà's Free-Word Painting—Patriotic Festival (1914) share striking similarities in their use of fragmented text and dynamic compositions, again both deeply rooted in the futurist desire to break with traditional art forms and convey the energy and chaos of modern life. Carrà’s Free-Word Painting—Patriotic Festival used fragmented typography and imagery to communicate a more specific nationalistic message, celebrating Italy’s militaristic and patriotic fervor in the years leading up to World War I (Ostendorf, 2001). This aligns with the nationalistic ideals of the time, particularly Italy’s desire to reclaim northern territories such as Trieste and South Tyrol (Mosse, 1990). While both works employ visual fragmentation to convey a sense of motion and urgency, the purpose of Carrà’s piece is more overtly political, functioning as a piece of propaganda to encourage the Italian nationalistic agenda and push towards war. Marinetti’s design, though also politically charged, is part of a broader futurist ideology that advocates for radical change through the rejection of tradition and the embrace of technological progress. The technical process and love of machines are emphasized with his use in the design with the use of parole in libertà, the abrupt stylistic choices appear random. Marinetti’s typographic design for Les mots en liberté futurists foldout again employs parole in libertà. The font changes happen without any clear ratios, and the curves of the design degrade inconsistently, lacking any sense of calculated order amidst the chaos. The same is achieved through Carrà’s piece using the circular nature and faux shadowing to create an image of a frontward facing airplane and its propellers. Marinetti’s design is a direct challenge to the viewer, attempting to engage them with curiosity, while Carrà’s work may have invoked a sense of pride or unity against opposing forces, urging the viewer to align with the fascist cause. Despite these differences, both works serve as visual tools that use typography not only as a means of communication but as an active force in shaping the viewer's emotions and beliefs with a distinct approach to art and design.

In both Marinetti’s Montagne + Vallate + Streets + Joffre (1919) foldout from Les mots en liberté futurists and Gino Severini’s Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin (1912) we see the repeated themes from all of the works analyzed above. Marinetti’s use of parole in libertà and Severini’s mixed media painting/collage with nationalistic themes that relay fascist ideologies. Through these works, the Futurists sought to both celebrate and manipulate the cultural and political currents of their time, laying the groundwork for the more overtly propagandistic uses of art in the years to come. A difference Severini’s work had from the other fine art discussed above is that it is depicting a club in Paris, France. While this work is previous to both world wars, it is not something that would have been approved by the nazis or fascist powers of that time. As time went on into the world wars and societal normalities in Europe became more conservative and restrictive, Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin, would have been deemed as inappropriate (Ostendorf, 2001).

What all of these artists, poets, politicians, and their consumers had miscalculated was the belief that their art, their life, was the exception: ‘I am privileged enough to be an individual’, but there is no individualism under fascism, capitalism, or white supremacy. Individualism, even by the same people producing propaganda or the people who benefit from it, is not allowed. What we see extremists of the early 1900s and today is that they vote or complete actions against their own best interest. Those who live as part of the favored group may think they are safe, but the system that thrives on exclusion and control is built on fear of those who are secure in their individuality and eventually, fear of the ones who helped build it. The system consumes itself, and no one is exempt, not even those who are convinced that they are protected by the walls they helped to build. History is riddled with examples of those who believed they were invulnerable, only to be swallowed up when the regime's need for compliance outweighed their momentary value. Mussolini, once the unchallenged dictator of Italy, was ultimately discarded by both his allies and his own regime arrested, and executed when his utility to the fascist cause had ended, illustrating the brutal fragility of power under tyranny (Ostendorf, 2001). Fascism doesn’t value the artist, the thinker, or the individual. It uses them and spits them out once they no longer serve the collective agenda. No matter how much dedication an individual has to their cause, human nature is a threat to the system.

They will use you, take your propaganda that you made for them, for free, and when they want to put your art, yourself-expression, into the “degenerate art” exhibition, they will turn their head to look away from you and

Works Cited

Antliff, Mark. “The Fourth Dimension and Futurism: A Politicized Space.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 82, no. 4, 2000, pp. 720–33. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3051419.

Bott, Adrian. “‘I Never Thought Leopards Would Eat MY Face,” X (Twitter), 16 Oct. 2015, 4:18 a.m.

Bowler, Anne. “Politics as Art: Italian Futurism and Fascism.” Theory and Society, vol. 20, no. 6, 1991, pp. 763–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/657603.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. The Futurist Manifesto, 1909.

Meggs, Philip B. Meggs’ History of Graphic Design. 5th edition Meggs, Alston W. Purvis. Wiley, 2016.

Mosse, George L. “The Political Culture of Italian Futurism: A General Perspective.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 25, no. 2/3, 1990, pp. 253–68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/260732.

Orban, Clara. “WORDS, IMAGES AND SIMULTANEITY IN ‘ZANG TUMB TUMB’ AND ‘PROSE DU TRANSSIBÉRIEN.’” Romance Notes, vol. 33, no. 1, 1992, pp. 97–105. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43802180.

Ostendorf, Berndt. “Subversive Reeducation? Jazz as a Liberating Force in Germany and Europe.” Revue Française d’études Américaines, 2001, pp. 53–71. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20874822.

Poggi, Christine. “Folla/Follia: Futurism and the Crowd.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 28, no. 3, 2002, pp. 709–48. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/343236.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Boccioni, Umberto. Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913. 2008

Tyson, Laura. Degenerate Practice: Inconsistencies in Repressive Regimes' Cultural Policies Against Avant-Garde Art. Diss. 2011.