Disclaimer: The ideas collected here are perfect for usage by anti-racism students who want to spark effective conversations with newly awakened “white people” who, for the first time, are feeling racial stress.

Photo by Anna Shvets

P.S. I call “white people” European Americans. (Dear anti-racism students, the first lesson you give may be why "European American" is a better term than the race-generating concept of calling human beings “white.")

Let me start by telling a story. I learned this from an insightful European American living in a modern sundown town. At the time of this story, the small city in Oregon called Ashland housed 22,000 residents, of whom 91% were European American.

Having just returned from a transformative experience at the Beloved Music Festival, I wanted to create a space in Ashland: a safe space for Black people inside of a hostile white environment. The issue, as was pointed out to me, was that residents did not perceive Ashland as a “hostile white environment.” In their minds, everyone was already safe. The fact that so few Black people chose to live in Ashland was the result of personal choice, not intentional, coordinated intimidation from the residents.

“You have to explain why,” I was told. “I know you know why. I know why. But they—in their own minds, the white people that live here—do not know why a sanctuary from them is needed.”

What is the why? The question is, why are they, as “white people,” experienced as dangerous by Black people?

To answer that question, I have to tell you a second story.

I am Generation X. I was born and raised in Anchorage, Alyeska (Alaska). Alyeska is the Athabaskan word for the Anchorage area. European American settlers could not say the word properly upon first contact and said “Alaska” instead. Because I grew up around Native people, I try my best to use Indigenous words when appropriate.

Anchorage is the United States’ most multicultural city. Thanks to the Alaskan Native Settlement Claims Act (ANSCA) of 1971, which returned 80 million acres of land stewardship to Indigenous people, assimilation to Western ways is minimized. Yes, technology exists, like cellphones and snow machines (mobiles). And, yes, a subsistence lifestyle—i.e., traditional hunting and gathering—happens side-by-side with the three concrete jungles of Juneau, Anchorage, and Fairbanks.

My family is from Louisiana. When I was 12, I met my maternal grandmother. Her name was Hazel. Nobody called her that. Her name was pronounced “hay zah.”

Mama Hazel patiently listened to me rattle off my stories about the last frontier. At some point, she asked me to stop talking, go into the living room, and open her Bible.

I knew exactly which Bible she was talking about. It was the biggest Bible in the house—a coffee table Bible. It looked expensive, with fancy colonial-era pictures throughout.

Because I was precious and listened to my elders, I knew Mama Hazel did not trust banks. She survived the Great Depression! Instead, she trusted Jesus. So, I followed her instructions and opened her Bible, thinking I was going to find dollar bills stored between the pages like a savings account.

That’s not what I found.

What I found were postcards. Old postcards with pictures of burned and hanged bodies.

“Mama Hazel,” I said with a trembling voice, “what are these?”

“Your family members,” she answered soberly.

From her, I learned about lynching. My maternal grandmother was born under Jim Crow in 1911. When she was 8, Red Summer happened. (If you don’t know what Red Summer was, Google won’t do this historical event justice.)

She was 44 when Rosa Parks started the Montgomery bus boycott.

She was 57 when Dr. King was assassinated.

Though I knew nothing about segregation and lynching firsthand, she did. One of my uncles died by lynching.

What remains seared into my brain wasn’t just what my grandmother said—it was how she said it and the look that crossed her face as she spoke.

Mama Hazel did not trust European Americans. To her, they were monsters to be survived.

Because I have no experience living inside a white body—as a white man, white woman, white child, or white queer person—I don’t know how it feels to be trapped inside the collective trauma of Black people. Whenever a Black person like my grandmother interacts with you, it is fraught with grace—and grace alone. Mama Hazel is the one overcoming what you, in your white body, represent. She is the one doing all the work. Because the United States of America is a racial caste system, the threat you pose to her remains unchanged.

Photo by Willian Santos

It is here where most, if not all, European Americans become overwhelmed with “big feelings.” They give up. From what I am told, “I feel helpless. There’s nothing I can do. I don’t have the power to change society. I’m scared of white supremacists too—and to think that’s how I am seen? That level of fear—I just don’t know what to do about it. So, I close down. I have to. I don’t want to feel evil. I don’t want to feel bad about being white. I know what happened to your grandmother happened, but I don’t want to pay the price for what those white people did by you choosing not to trust me or be my friend or do business with me. I don’t know what to do. I don’t feel safe around a lot of white people, just like you don’t. I hate that!”

In 2020, when I accepted the challenge to invite European Americans to go on their healing journeys, I had no idea the weight of what I was asking of them. Some days, I acknowledge that I still don’t. In an effort to help, I reached out to

, an Atlanta-based pro-humanity educator. Together, we crafted a four-week class designed to provide guidance and community through those big feelings.The name of the class is Radical Self-Love Meditations for European Americans Walking Out of White Supremacy Culture.

It takes a deep reservoir of courage to do this work. Why?

Because most, if not all, European Americans are conditioned through childhood trauma to comply with white supremacy culture. How does this show up? At its most basic level, compliance manifests as profound respect for the taboo against talking about race or your individual relationship to it.

Over and over, anti-racism students complain that when they confront another European American about race or white supremacy, two outcomes follow: Either the European American rages internally and shuts down, refusing to talk, or they rage externally and become violent to enforce the taboo.

Consequently, there is little trust that millions of European Americans—especially Trump supporters—want to leave white supremacy. Most associate it with technological advances. Dismantling white supremacy sounds like dismantling their access to toilets, electricity, streaming services, or “opportunities.” Attacking white supremacy lands as a personal attack.

Let me end by addressing what European Americans demand most from me when anti-racism is raised: “What do you want me to do?”

As a Black man living in the United States, I want you—in your white body—to face the shadow of what whiteness means in your subconscious. I don’t know what that means for you, nor does telling me help. Find another European American to explore what whiteness means to you. That is where the real work—in your nervous system—lies.

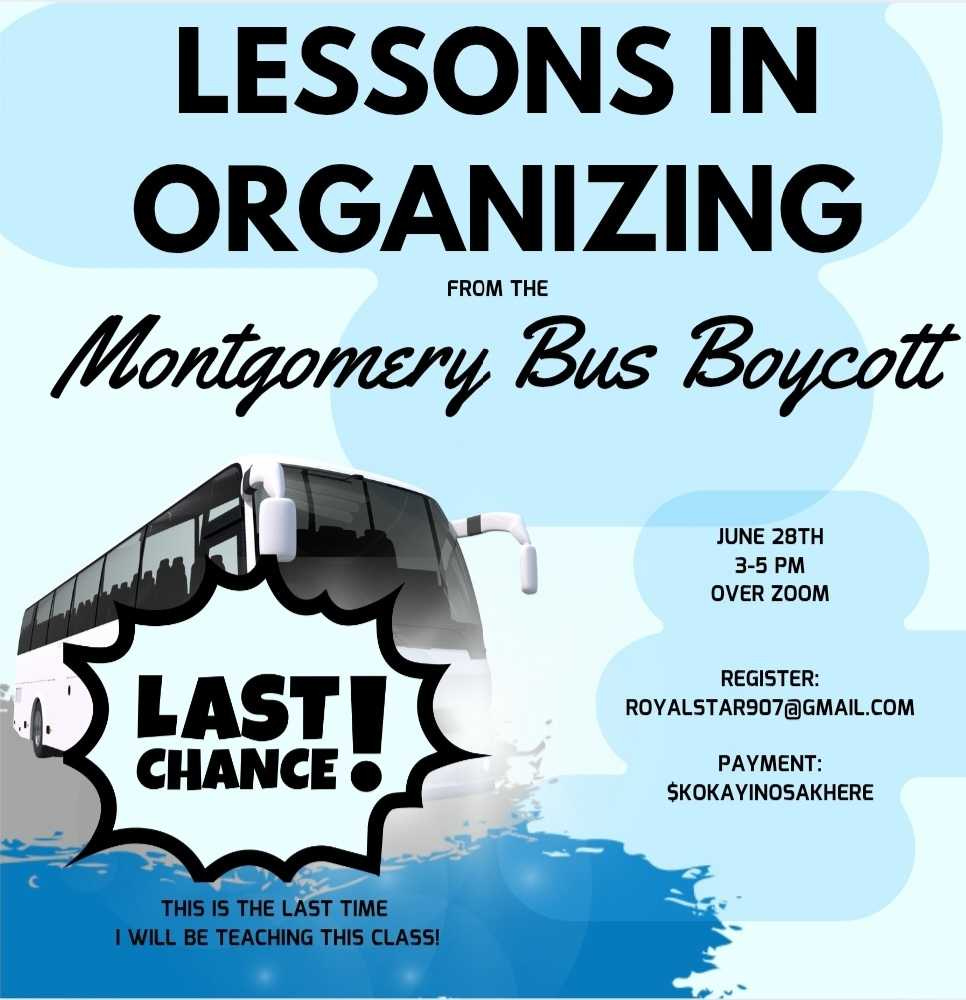

UPCOMING CLASSES

Email: royalstar907@gmail.com to register